Under Hezbollah's Thumb - The Back Story of Kiryat Shmona

July 19, 2024 - Issue #55

Little more than fifty years ago, three Palestinian terrorists crossed Lebanon’s border with Israel, descended the hill in front of them, and then surreptitiously entered Kiryat Shmona. They planned to seize a school building filled with students to force Israel to release 100 terrorists in its jails.

But it was Passover. The school was empty.

Determined to shed innocent blood, they then set their sights on a nearby apartment building. There, they found adults but also a few of the younger targets they sought at the school. Some they shot, their bodies later found littering staircases and halls. And some, just children, they flung out third floor windows to their deaths. One nine-year-old girl survived by hiding while her mother, sister, and two brothers died at the hands of those murderers. When Israeli soldiers attempted a rescue, the terrorists died when a backpack one wore that was filled with explosives blew up. In the end, eighteen Jews were murdered, eight of them youngsters. Fifteen more were wounded.

Unfortunately, those terrorists were not the only scourge Kiryat Shmona has endured. Between 1968 and 1996, 3,839 rockets targeted Kiryat Shmona, the only difference among them being that by 1996 Hezbollah’s terrorists fired them them rather than Palestinian terrorists. More rained down on the city in 1999. Then, in 2006, Hezbollah fired another 1,000 rockets at Kiryat Shmona. Civilians there had to choose— temporarily evacuate or hunker down in sparse bomb shelters. Iron Dome had not yet been invented.

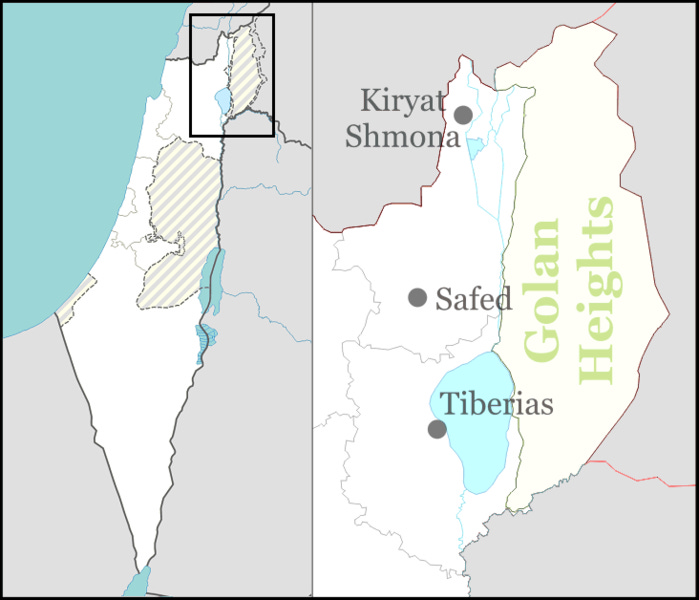

Today, Hezbollah is again targeting Kiryat Shmona. Less than two miles from Lebanon and nestled at the bottom of a hill that slopes away from the border, Kiryat Shmona is easy pickings for Hezbollah’s weapons.

That is why Israel ordered its 23,000 citizens to evacuate nine long months ago. Some of them remain in hotels they were sent to, including the one in which I stayed in Tel Aviv where I saw many evacuated families. Others have found temporary housing elsewhere. And a number of intrepid souls never left or have filtered back into the town.

News reports I’ve read and watched, confirmed by my personal observations several months ago, unanimously state that Kiryat Shmona is now barren, devoid of any semblance of city life. Its businesses are boarded up, and signs of damage, fires, and explosive impacts from the hundreds of rockets, anti-tank missiles, and drones that have targeted the town are everywhere. There, only the weeds and unkept shrubbery thrive. Now, the only thing that its few remaining inhabitants can count on is that Hezbollah will continue firing at them—nearly every day and every night—making normal civilian life in Kiryat Shmona impossible.

But does this loss of home, this loss of sovereignty, focus your thoughts on the need to deal with Hezbollah—the perpetrators of this calamity? Perhaps not. Nor would I blame you if that is the case. Amid all that Israelis have endured in this war, and the suffering in Gaza that Hamas is responsible for, what Hezbollah sends winging Israel’s way on a daily basis is not on the emotional radar screen for many—especially because even though 100,000 inhabitants of northern Israel have been displaced, the death count there has so far been comparatively small. And so, the daily drumbeat of war becomes ho hum, drowned out by the onslaught of new, more titillating events.

But what was once thought a temporary evacuation now has taken on the look of something permanent unless Israel will proactively act to recover the huge swath of its land rendered uninhabitable by Hezbollah. Can Israel afford not to? No! Because even an inch surrendered will become a foot when Hezbollah extends its reach which it can easily do, and then that foot a mile, and then a region—and then that surrender will lead to the end of the nation. Yet, human nature being what it is, even repetitive mention of the trials and tribulations of an unfamiliar location with a foreign sounding name will not stir the souls of people thousands of miles away who know nothing of the place or its people. Therefore, since Hezbollah frequently targets Kiryat Shomna and its name is often mentioned in the news, I thought it worthwhile to share with you a little about its history in hopes that Hezbollah’s perfidy will move you to act as it has me.

Kiryat Shmona’s Backstory

My first times passing through Kiryat Shmona, I viewed it as one of those towns you drive through on your way to somewhere else. Along the main highway that heads north and south and that splits the town, scattered shopping centers and storefronts line both sides of the road. Some more modern; others much older and quite worn. Other than stopping once to buy a shawarma from a roadside establishment that I will charitably call a deli, I had always driven through the city toward Kfar Giladi or Metula, a few miles farther north, or would turn east towards one of the many border kibbutzim in the area or even to the Golan Heights perhaps ten miles away. Never did I explore the residential communities, buildings, museums or other parts of Kiryat Shmona east or west of the main highway. Thus, all I knew of the town was gleaned from bits and pieces of old news reports of the deadly missile attacks it endured over the decades.

That all changed in 2018 after I met Yamit Yanai Malul—a woman of moderate height, pleasant appearance, and who is loquacious, charming and determined to improve the plight of Kiryat Shmona’s residents.

We met at a Cafe Cafe coffee shop—yes, that was its name—located at the southernmost part of Kiryat Shmona. To get there I drove west from the Golan Heights rather taking my normal route from the south. This time, Kiryat Shmona looked beautiful, nestled into the hillside to its west. While much of what we spoke about is not relevant for this essay, what she had to say kindled my desire to learn more about Kiryat Shmona’s history. What I learned captivated me and I hope it will help put a memorable face on Kiryat Shmona for you.

Until the the 1948 Arab-Israeli War ended in 1949, an Arab village called Al-Khalisa was located where Kiryat Shmona is now. One consequential moment some of its Arab inhabitants had participated in occurred thirty years earlier, when they joined in the attack on nearby Jewish Tel Hai during which Joseph Trumpledor died at the hands of the Arab marauders. Trumpledor’s reported deathbed statement, “It is no matter, it is good to die for our country,” made him a legend in Israel.

After Israel won the war in 1949, the residents of Al-Khalisa fled. Whether they chose to leave, were forced to leave by victorious Jewish forces, or something in between, is a subject for endless argument well beyond the scope of what I seek to explain. But as a result, the area lay vacant.

Meanwhile, kibbutzim in the region and Israel’s central government wanted to advance Jewish settlement of the area, in part to hold the border, but lacked volunteers. Therefore, on July 18, 1949, Israel’s new government literally deposited fourteen Jewish Yemenite families at Al-Khalisa. A month later another group of similar size joined them. All were refugees—a few of the 700,000 Jews that would eventually flee Arab nations that made life impossible for them to remain in their homes after Israel won its war for independence. At first the community the Yemenites inhabited was renamed Kiryat Josef, in memory of Trumpledor. By the end of the year, the number of Jewish refugees from Arab lands living there grew to 200 and plans were made to build hundreds of housing units to accommodate many more.

At this point, it is important to acknowledge the backgrounds of the people living in the area. Nearby were many kibbutzim, whose members were for the most part Ashkenazi Zionists. As such, they were more secular than religious and largely came from Europe or Russia. And although many escaped pogroms and harsh government restrictions where they formerly lived, most had come to Palestine to build a new Jewish nation through physical labor and shared sacrifice. To accomplish that, they came to kibbutz life by choice. For them, their kibbutz was everything. Members shared both the backbreaking work required for their survival and the fruits of their labors. Governance was by majority vote, and when there were opportunities for leisure, their social structure used those moments to foster bonds within the community. This led to them being somewhat insular as a community by default. Not from bad intent but from a need and desire for mutual support and enhanced socialization that would ensure communal success.

On the other hand, the Yemenites who first came to Kiryat Yosef had no say in where Israel’s government placed them. As was the case all over Israel where Jewish immigrants from Arab countries throughout the Middle East and North Africa were flooding the country. Known as Mizrahi or Sephardi (I shall call them Mizrahi), their ethnic traditions were different than the Ashkenazi. Often more religious, they also lived differently than the Ashkenazi, had different traditions, had different family structures, and had different attitudes in general. Physically, they bore a closer resemblance to the defeated Arabs than the victorious European Jews. And when they fled, or in many cases were evicted from their homes, they left behind all their belongings. No matter their previous economic status, they were poor refugees upon arriving in Israel. Nevertheless, while Israel did not have the resources to properly receive them, it welcomed them anyway.

It also needed the Mizrahi to help populate and hold the land as a Jewish state.

Israel had just won a war started by the Arabs in its midst and the Arab nation surrounding it. But victory had taken a toll. Israeli forces had suffered many deaths and much more wounded. The fighting had destroyed many physical structures, and for years all the resources available to Jews in Palestine had been directed toward procuring the means to fight rather than live prosperous lives. Now, Israel sought to recover its economy and infrastructure while simultaneously trying to settle what became more than a million refugees arriving within a decade of the state’s establishment. Complicating matters, Israel saw its population double during the first three years after its victory, with the arrival of more than 600,000 Jews. And its population already had included many refugees from the years before the war started. Of the Jews who arrived after the war, some were Holocaust survivors, but many were Mizrahi from Arab lands.

Israel’s government identified two problems and tried to solve both in one stroke. First, it needed somewhere to put the refugees. Second, it had to figure out how to settle the areas in the north and the south that were crucial from a security and economic perspective for the state to hold but were relatively far from the populous center of the country centered on Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa. The government’s solution was to create transit camps to house the immigrants—especially those from Arab lands of whom many in Israeli society looked down upon.

As such, the government sent many Mizrahi immigrants to the Negev, including Beersheba. Others it settled close to Gaza, like in Sderot. And some it sent to the new transit camp at Kiryat Yosef.

The influx of Mizrahi people at Kiryat Yosef stirred debate within the local kibbutzim in late 1949 and into 1950. What kind of community did they want Kiryat Yosef to be—an urban area or an agricultural community? Many of the older pioneers in the region—some of whom had risked their lives guarding Jewish communities well before there was a Jewish state—pushed for an agricultural community. They did not want to spoil what they saw as the “special character of the area.” Eventually, though, most agreed on an urban vision for Kiryat Yosef. They saw need for laborers to help develop the area and drain the nearby Hula swamps. Meanwhile, the government didn’t wait for their decision. It had already decided that the transit camp at the former Arab village of Al-Khalisa would become a city. Then, in June, the name of Kiryat Josef was changed to Kiryat Shmona. Rather than naming the city after just Joseph Trumpledor, now its name would honor all eight who had died at Tel Hai.

And so, what started as a transit camp grew as an independent community with its own municipal government. Between the autumn of 1950 and the end of 1951, the national government poured thousands of immigrants, almost all fleeing persecution in their homelands, into the city. They came from Romania, Iraq, India, Persia, Hungary, and a few at first from North African countries such as Morocco. Many more Moroccans came later. During that period, Kiryat Shmona’s population swelled from 800 to 4,000. From there it continued to grow. A few years later, Kiryat Shmona grew into the largest community in the Upper Galilee and one of the largest transit camps in the country.

But poverty overwhelmed its inhabitants and public services collapsed under the strain of such rapid growth, which Israel’s government, short of resources, failed to adequately address. Area kibbutzim pitched in to help, but not enough to alleviate the suffering. There were just too many immigrants to help. The dining hall was built to hold 100 kids. Soon there were 350. The growing numbers overwhelmed the teachers and all others who tried to assist.

Nor could the newcomers earn enough money to improve their standard of living. Making matters more difficult, some had many children leaving their salaries insufficient to cover the costs of feeding and housing their families. As a result, living conditions were harsh, especially in the summer when up to eight beds crowded rooms built for far fewer. That, coupled with the heat and poor sanitary conditions, fostered the spread of illness.

Not surprisingly, the immigrants, mired in a hopeless situation not of their choosing, became less appreciative and increasingly angry. They were not sympathetic regarding Israel’s struggle to settle so many newcomers on the backside of a devastating war that left it with few resources. Nor were they accepting of the prejudice they encountered from their fellow Ashkenazi Jews. At the same time, many of the kibbutzniks saw the townspeople in Kiryat Shmona as lazy, backward, and less capable.

In my mind, both sides were wrong and right. The situation was impossible and the cultural differences vast. The new immigrants had chosen to come to Israel (many because they had no other option) because of the treatment they were subjected to in their home countries but had few choices or resources upon arrival. In Israel, they were sent, with little support, to build new lives in ramshackle homes near the borders where their presence, like border kibbutzim before, served the nation. Having just fought a war for their survival, many kibbutzim accepted their responsibility to help yet lacked the resources to alleviate all the suffering while also maintaining and developing their own communities. Human nature being what it is, it’s natural that Kiryat Shmona’s residents became more frustrated, just as the kibbutzim grew more resentful. And so, troubles began in those early years, troubles that continued through October 7. Kiryat Shmona, plopped in the middle of kibbutz owned verdant fields that served as a constant reminder of what they don’t have, struggled with its economic hardships.

Nevertheless, despite Kiryat Shmona’s ongoing struggle to obtain more assistance from the national government and more land for growth which would give rise to a greater tax base that would provide revenue for needed programs, there were some rays of hope. One was the joy and great pride Izzy Sheratsky, a wealthy Tel Aviv born entrepreneur, brought to the city. He took over the two soccer teams then in Kiryat Shmona, merged them into one, and instituted an ironclad rule while pursuing his mission. His mission was to win by developing homegrown soccer talent. To do so, he invested in the city’s youth programs. His ironclad rule was that all players had to live within city limits. At first, the team played in a fourth level, bush league in Israel. In a small country like Israel, that was the lowest of the low. But in 2012, the club won Israel’s highest level national championship and qualified to join Europe’s Europa league. Quite a success story amid all the decay and danger.

Nevertheless, in 2018 when I first studied Kiryat Shmona, it was clear that many of the city’s residents were still mired in poverty. Nor did they feel safe. Memories of terror and the ongoing threat Hezbollah posed weighed on their minds. Proof of that came from Yamit, who had grown up during a time when Palestinian and then Hezbollah Katyusha rockets and mortar shells frequently exploded in the city. Then, while we spoke, at Café Café, a loud sound from outside suddenly punctuated our conversation. “I’m hearing now,” she said, “the motorcycle, [it sounds like a shell]. When a missile [comes] it is like a whistle sound.” Yamit’s reaction was no surprise, given that dating back to when she was little, she knew how close incoming fire would hit by the sound.

Fortunately for Yamit, her home contained a shelter. That was unusual for then, and even now Kiryat Shmona has perhaps fifty prevent of the shelters it needs for its people. “I’m still hearing” she said speaking of her father, “his voice, the yelling, go down. We didn’t have a siren. We had to listen and when we hear[d] the whistle then we go down.” Then she said, “A lot of people in Kiryat Shmona [were] killed because they didn’t get to the shelter, they didn’t have the time. It was crazy.”

It's even crazier today. Those remaining in town have no more than ten seconds to reach a shelter because of the location’s proximity to Lebanon and the type of weapons now used by Hezbollah. Often the boom of the bomb is heard before the alarm, making finding shelter more aspirational than achievable.

And so, life in Kiryat Shmona is intolerable today. What was impoverished before lays empty today. Families are gone, economic activity is absent, and only a ghost town marks the location where 23,000 people once lived their lives, and due to Hezbollah, may never return if the situation does not change soon. And the same is true for the area’s kibbutzim. They too lay empty. Monuments to Zionism’s one-time success now teetering. Both town and kibbutz leaders fear that their people will not return and their way of life will be over—leaving them poorer for their loss and Israel weaker for their flight.

And so, today, the Mizrahim in Kiryat Shmona and the Ashkenazi border kibbutzim are in the same boat, rowing together to demand that Hezbollah be neutered and their hopes and dreams returned to them.

My next newsletter will include an analysis regarding Hezbollah of the potential impact on Israel’s decision making of the effort to convince Biden to give up his reelection campaign, Israel’s political clock and clues thereto from Bibi Netanyahu’s speech before congress scheduled for July 24.

Also, if you have an interest in the danger Hezbollah presents and how it came to be, you might consider purchasing my book which can be obtained on Amazon here.

Israel-Hamas War—July 19, 2024

Explosive Drone from Yemen Hits Tel Aviv Apartment, killing One Man, Wounding Others—Written by Emanuel Fabian for Times of Israel—July 19, 2024

We Too are Fighting a War, Right Here in Melbourne—Written by Sharonne Blum for the Times of Israel—July 6, 2024

Disaster from the North—An outstanding interview of Matti Friedman from June 28, 2024. It is a long read, but a revealing one, from an author for whom I have tremendous respect.

Israel is Losing the North—Written by Michael Oren for the Times of Israel—July 11, 2024

Analysis: A Greatly Expanded Arsenal Means This is Not the Hezbollah of 2006—Written by multiple authors for Foundation for Defense of Democracies Long War Journal—July 9, 2024

Inside Hamas: How the Terrorist Organization Uses Guerrilla Tactics to Wage War—Written by Darcie Grunblatt for the Jerusalem Post—July 13, 2024

How Hamas Is Fighting in Gaza: Tunnels, Traps and Ambushes—Written by Multiple Authors for the New York Times—July 13, 2024

From "Phew, We Might Just Avoid War in the North" to "We Need to Go to War, and Right Away"—Written by Daniel Gordis for his newsletter, Israel from the Inside—July 11, 2024

From Hamas Stronghold to Wasteland: What Does it Mean to Defeat the Enemy?—Written by Herb Keinon for the Jerusalem Post—July 9, 2024

Hezbollah Adopts Low-tech Strategy as it Tries to Evade Advanced Israeli Surveillance—Written by Reuters and TOI Staff—July 9, 2024

Why There Will Be No Mega-war in the North with Hezbollah, at Least This Year - Comment—Written by Yonah Jeremy Bob for the Jerusalem Post—July 12, 2024.

I disagree with the opinion expressed in this article regarding the likelihood of war (I agree regarding its devastating potential) but provide it for your evaluation.

Israel’s Struggle with Hezbollah—A War Without End is now available in eBook and hardback format on Amazon and IngramSpark. This compelling narrative explores Hezbollah’s origins and cancerous growth, traces Israel’s response, and reveals Israel’s present readiness to meet Hezbollah’s challenge.

Cliff Sobin

Important Link—Alma Research and Education Center: Understanding the Security Challenges on Israel’s Northern Border